Taking on the Status of Quotas: A Review of “Creating Equal”

May 22, 2000

by James Webb, The Wall Street Journal Op-Ed

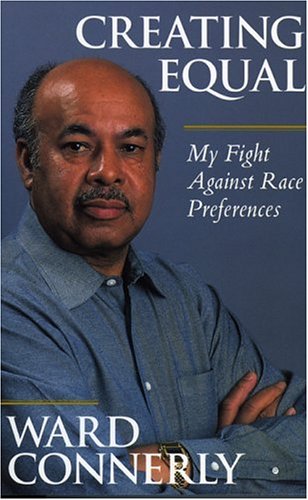

For years the debate over affirmative action has desperately needed a “truth teller” whose credentials could not be demeaned because of his own ethnic background or because of allegations of personal bitterness. Ward Connerly, a regent of the University of California and now the author of “Creating Equal,” (Encounter, 286 pages, $24.95) fits this bill.

A self-made businessman and political operative of mixed African, European and Native American descent, Mr. Connerly became convinced that affirmative-action policies were harmful to the nation, including to minorities themselves. Unlike pundits who remain content to write hand-wringing editorials or trade words on Sunday talk shows, Mr. Connerly took action. The force of his will and intellect was the major determinant in ending affirmative action at the University of California in 1995. He then became the key proponent of Proposition 209, which ended racial preferences in California’s state government. He is now the nation’s leading proponent of truly race-neutral policies.

As one might expect in this Orwellian age, the very elements in his background that gave Mr. Connerly credibility in the larger debate were turned against him, causing him to become the object of vicious and continuing attacks. Focusing on such matters as his marriage to a white woman and his membership in the Republican Party as evidence of his disloyalty to minorities, affirmative-action proponents love to characterize Mr. Connerly as a “white wannabe” and “Uncle Tom” — in short, as a traitor to his race.

“Creating Equal” is partly Mr. Connerly’s reply to those attackers and partly an account of the personal journey that has brought him to his current convictions. One finds in the pages of this book a strong personality who is not afraid to confront his critics, from Jesse Jackson (“so out of step . . . that he sounded like a flat earther”) to Gen. Colin Powell (“Powell had many things to contribute to the Republican Party but an original or profound view on race was not one of them”). The book also shows a measured approach to other social questions (he favors, for example, domestic-partner benefits for gay couples) that in the end convinces an objective reader that Mr. Connerly’s views on race relations are decades ahead of the Jacobins who have foisted the affirmative-action regime on this country.

Affirmative action, which originally sought to repair the state-induced damage to blacks from slavery and its aftermath, has within one generation brought about a permeating state-sponsored racism that is as odious as the Jim Crow laws it sought to countermand. A Soviet-style bureaucracy of political commissars now monitors every level of our society to ensure that racial and gender “diversity” matches pre-ordained models, using the awesome powers of government to make certain that white males are not “overrepresented” in education, employment or government contracts.

And yet, despite billions of dollars spent on such policies and the “people watchers” charged with implementing them, the results have been both ludicrous and sad, with every nonwhite ethnic group enjoying favoritism while a significant part of black America remains mired in the underclass.

The breadth of this folly will no doubt stun future historians. As Mr. Connerly notes, the California Legislature defined “socially disadvantaged persons” eligible for government preferences as “Women, Black Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans (including American Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts, and native Hawaiians), Asian-Pacific Americans (including persons whose origins are from Japan, China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Korea, Samoa, Guam, the United States Trust Territories of the Pacific, Northern Marianas, Laos, Cambodia, and Taiwan).” This definition is similar to those used in federal programs, including the highly lucrative Section 8(a) set-aside programs for federal contracts.

It is today difficult to have a rational public debate about how this policy has gone awry. Such debates are made even more difficult because affirmative-action programs have scarcely affected the more advantaged white groups, who evince a great reluctance to criticize the (usually middle-class) minorities who have joined them in the “new elite.” Enter Ward Connerly, who had the temerity to declare not only that affirmative action has become a sham but that “well meaning liberals” are defending a “morally incoherent policy . . . that benefits a handful of middle-class blacks” while failing to address “the underclass seething helplessly in the inner cities.”

A weakness of Mr. Connerly’s book is that it barely touches on the deep socio-economic divisions among white American cultures, which make the entire premise of affirmative action — that white America is a fungible monolith from which benefits to minorities can be drawn — fallacious. In the zero-sum game of college admissions and job selection, the less successful white cultures have fallen further behind as a veneer of minorities have joined the elites. Nor does Mr. Connerly discuss how Asian-Americans, who in states such as California seem to have been held back by affirmative-action policies, have nonetheless benefited greatly from set-asides in government contracting. But in fairness, these issues are beyond the scope of Mr. Connerly’s story.

This warmly personal, highly readable book allows Mr. Connerly the opportunity not only to put his background into context but to persuade the reader of the sincerity of his views and thus of his motives. As he sums up at the end of one chapter: “I had done my part to enhance the image of black Americans as being independent and resourceful, confident in America’s ultimate fairness, and capable of finding their own way to success and fulfillment.”

Memo to Al Gore and George W. Bush: Read this book.