Foreign Policy & National Security

Can We Still Rely On An Old Ally? The Philippines

May 25, 1997

by James Webb, Parade Magazine

Contributing Editor James Webb is a former US Secretary of the Navy, and a recipient of the Navy Cross and the Silver Star for his service in Vietnam. He is the author of four novels, including the Vietnam classic “Fields of Fire.” A frequent traveler to East Asia, he currently is working on a novel about the Philippines in World War II. With the increase in concern over the military and economic growth of China and its effect on the Asian-Pacific nations, we asked Webb to report on the significance of the Philippines, one of our strongest allies in the region, since the U.S. has reduced its military presence there.

Contributing Editor James Webb is a former US Secretary of the Navy, and a recipient of the Navy Cross and the Silver Star for his service in Vietnam. He is the author of four novels, including the Vietnam classic “Fields of Fire.” A frequent traveler to East Asia, he currently is working on a novel about the Philippines in World War II. With the increase in concern over the military and economic growth of China and its effect on the Asian-Pacific nations, we asked Webb to report on the significance of the Philippines, one of our strongest allies in the region, since the U.S. has reduced its military presence there.

I am sitting in a richly paneled, book-lined greeting room inside historic Malacanang Palace, waiting to interview Fidel V. Ramos, the 12th president of the Republic of the Philippines. I have a question to ask him that is vitally important to America’s future in Asia:

As Asia changes, can the U.S. still count the Philippines as an ally?

The last time I met with Ramos was in 1987. I was U.S. Secretary of the Navy. He was chief of staff of the Philippines’ armed forces. A year before, the Philippines had gone through the trauma of what they now call the “People Power Revolution,” ousting the martial-law government of Ferdinand Marcos. Ramos had been a key player in that revolution, and it was clear to me that his future was larger than his role as the nation’s chief military officer.

The Philippines was a different country following the chaotic revolution. Its economic growth was at a standstill. Filipinos could be seen living in boxes and sleeping in makeshift hammocks in trees along Manila Bay. The U.S. presence was most visible in its military installations at Subic Bay and Clark Air Force Base, which had been a part of the Philippines landscape for nearly 90 years.

At that time, the Soviet Union kept its largest fleet in the Pacific. At Vietnam’s Cam Ranh Bay, the Soviets regularly based two dozen warships as well as an imposing air force. At our 1987 meeting, I had given Ramos a photograph of a Soviet MiG that was trying to intimidate a U.S. Navy aircraft in international air- space between Vietnam and the Philip- pines. My message had been simple: The Philippines should not lose sight of international dangers that were the consequence of its strategic location at the heart of the world’s most dynamic economies.

There was no disagreement on that point, although the West Point educated general emphasized the Philippines’ difficult domestic situation. I came away impressed and confident that he believed the Philippines ought to remain closely aligned with the U.S. I predicted upon my departure that Ramos would be president. In 1992 Filipino voters elected him to a single six-year term.

The country has prospered under his leadership. The Philippines, once the “sick man of Asia,” now boasts an economic growth of 7 percent a year. Per capita income has doubled in the last decade. A recent survey by the Far Eastern Economic Review ranked the Philippines as the best place to invest among 10 Asian-Pacific nations and the country least likely to experience political upheaval. Last fall Ramos was host to 18 world leaders, including President Clinton, at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum overlooking the former U.S. Navy base at Subic Bay.

The country has prospered under his leadership. The Philippines, once the “sick man of Asia,” now boasts an economic growth of 7 percent a year. Per capita income has doubled in the last decade. A recent survey by the Far Eastern Economic Review ranked the Philippines as the best place to invest among 10 Asian-Pacific nations and the country least likely to experience political upheaval. Last fall Ramos was host to 18 world leaders, including President Clinton, at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum overlooking the former U.S. Navy base at Subic Bay.

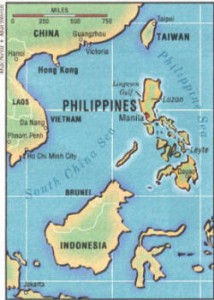

These advances have taken place in a dramatically altered international climate. The U.S. bases have been gone from Subic and Clark for five years. The Russians are no longer in force in Cam Ranh Bay. But the lowered U.S. presence has been matched by a looming threat: an energized and potentially expansionist China. The entire region is nervous and unsure of what the future holds. A large factor in the uncertainty is whether the U.S. in- tends to hold fast to its Asian interests.

These questions have particular resonance among the 70 million people of the Philippines. On the one hand, they are now adamant about showing their independence from the U.S.; on the other, they are proud of the role they have played as our friend and ally in World War II, Korea, Vietnam and the Cold War. China has been aggressively growing its military, particularly its naval forces. If China were to increase its bullying throughout the region, the willingness of “second-tier” countries such as the Philippines to join the U.S. in facing down such moves would be essential.

President Ramos enters the briefing room and greets me. He takes his seat at a wide wooden desk into which a glowing computer screen has been built. At 69, he is a pleasant, intense man whose seriousness is offset by dry humor and a pixie grin. Like most Filipinos, he has strong personal attachments to the U.S. But when asked about the U.S. and the Philippines as strategic partners, Ramos deflects the question.

The greatest continuing benefit of a strong relationship with the U.S., he insists, is trade. “The U.S. is our No.1 trading partner,” he declares, “still our No.1 investor.” Pressed, he volunteers that the other major connection between the two countries is “the people factor.”

“Filipino-Americans are our largest overseas population,” he says. “Filipinos of all ages love the United States. Unlike the Spanish [who colonized the Philippines for nearly 400 years], the U.S. put a nationwide educational system in place and emphasized the teaching of English.”

“Filipino-Americans are our largest overseas population,” he says. “Filipinos of all ages love the United States. Unlike the Spanish [who colonized the Philippines for nearly 400 years], the U.S. put a nationwide educational system in place and emphasized the teaching of English.”

Ramos is being coy, but he is not wrong on either count. Despite recent large investments by Japanese and Chinese companies, the U.S. accounts for 33 percent of the Philippines’ exports, 20 percent of its imports. U.S. companies also have earmarked $12 billion for investment in the next five years. And the “people factor” is enormous. An estimated 30,000 Americans visit the Philippines each month. And Americans of Filipino descent have become the largest Asian-American population, now about 2 million, the U.S. ambassador to the Philippines told me.

But Ramos declines to comment on U.S. — Philippines security interests. Asked about the threat brought by China, he anchors himself in Asia. He mentions the growing importance of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and concludes by saying, “We hope all the players will continue to be engaged. We are in the middle of all this, geographically and otherwise, and we must take a balancing position. The big players may have their competing interests, but we want to see stability.”

Ramos’ insistence on neutrality represents either careful diplomacy designed not to arouse the Chinese or a reluctance to see the Chinese threat for what it is. Either way, it sends a message that future Chinese aggression will be viewed as a “great power” issue rather than a regional concern.

If our alliance is weakening, it is because American government action is not matching the efforts of American business in this vital region, while the energy of other governments has increased. The U.S. military rarely operates in the Philippines anymore, and American diplomacy has been markedly uneven as it affects our national interests in the entire region.

By contrast, the day I arrived in Manila, the Chinese defense minister was wrapping up a lengthy visit by announcing a plan for future cooperation on defense issues. And Ramos, who last year performed the extraordinary feat of bringing internationally backed Muslim secessionists on the island of Mindanao into a substantive peace process-was leaving after our interview on a trip that would include India as well as key Muslim nations from Pakistan to Bahrain.

What of the future? At present, Ramos is precluded from running for reelection, and his term will expire next year. Curious, I posed the same questions to two younger leaders, both viewed to be future presidential candidates. Roy Golez is a U.S. Naval Academy alumnus who last year was named by the influential Philippines Free Press as the country’s outstanding congressman. Richard Gordon is the chairman of the Subic Bay Metropolitan Authority, a free-trade zone situated at the former U.S. Navy base.

Golez, 50, is a key ally of Ramos’. He was only 34 when Ferdinand Marcos selected him to be postmaster general. He aligned himself with Ramos during the 1986 revolution and now heads the key congressional committee that oversees the national police and the fight against crime.

Golez, 50, is a key ally of Ramos’. He was only 34 when Ferdinand Marcos selected him to be postmaster general. He aligned himself with Ramos during the 1986 revolution and now heads the key congressional committee that oversees the national police and the fight against crime.

Proud of his American ties, Golez nonetheless echoes Ramos on U.S. — Philippines relations. The greatest benefit of this relationship, he asserts, is trade, although the Philippines is also “looking at tie-ups with giants emerging in such countries as India.” Stating that “sentimental reasons” lead many Filipinos to view the U.S. as its most important strategic partner, Golez insists, “We must cope with the realities. Japan is very visible, with all its products dominating the market. The proximity of China, Taiwan and ASEAN and Middle East countries gives us both interaction and opportunities.”

How does he view the Chinese threat? “With caution,” says Golez. “It’s uncomfortable having a giant close to you.” But then he retreats to a historically inaccurate comparison- “China has no history of expansion and imperialism, unlike Japan and Western powers”-and predicts that China will be “a big but friendly, polite neighbor.”

Richard Gordon is less circumspect. Gordon, 51, grew up in Olongapo, bordering the former U.S. base at Subic Bay. His grandfather was an American soldier here who never went home. His father was the first elected mayor of Olongapo and was killed in 1967 in a political assassination. Later his mother, and then Gordon himself, was elected to the job. When the U.S. Navy left Subic, resulting in the abrupt un- employment of 42,000 Filipinos, Gordon led a group of volunteers who negotiated to turn Subic into a free- trade zone. Today Gordon oversees the vast complex, where more than 150 companies have now signed on.

Rightly taking credit for Subic’s new direction, Gordon says it has resulted in “a calmer, stronger relationship” between the U.S. and his country: “There are fewer things to blame on the U.S. when agitators wish to cause trouble.” At the same time, he is upbeat about the contribution of the former U.S. bases to regional peace: “The bases provided peace and prosperity for the entire region and contributed to winning the Cold War.”

Gordon is adamant that the U.S. remain a Pacific military power. “The Philippines has no real military capability,” he says. “China’s record on human rights and the growth of its military trouble me. If the U.S. pulls out of Okinawa, it will put the entire Asian- Pacific region at risk. Either a remilitarized Japan or an expanding China would be tempted to fill the vacuum.”

In these leaders, as with almost every Filipino, one finds an affection for the U.S. and a desire to continue our unique historical relationship. President Ramos speaks of the “people factor.” Congressman Golez predicts that “political and cultural forces” between our two nations will “become even stronger with the years.” But it’s Chairman Gordon who most accurately defines the problem: “The relationship between Americans and Filipinos remains incredibly strong. What is lacking right now are the same strong ties between our governments.”