Foreign Policy & National Security

Hunting Down Al Qaeda ~ A Report From Afghanistan

September 12, 2004

by James Webb, Parade Magazine

The four engine C-130 Hercules descends toward total darkness above Tarin Kowt in the plains of central Afghanistan, 70 miles north of the ancient capital of Kandahar. Its wheels finally bite into an unmarked dirt airstrip. The aircraft brakes hard, then taxis along the strip. Billows of dust engulf us. The rear door yawns open, and we trundle down the tailgate onto an eerie, empty landscape lit only by the brightness of the moon. As I step onto the runway, my boots sink into six inches of powder, so fine and dry that it might be talc.

The four engine C-130 Hercules descends toward total darkness above Tarin Kowt in the plains of central Afghanistan, 70 miles north of the ancient capital of Kandahar. Its wheels finally bite into an unmarked dirt airstrip. The aircraft brakes hard, then taxis along the strip. Billows of dust engulf us. The rear door yawns open, and we trundle down the tailgate onto an eerie, empty landscape lit only by the brightness of the moon. As I step onto the runway, my boots sink into six inches of powder, so fine and dry that it might be talc.

In the moonscape I can see the silhouettes of Marines moving through a small city of tents, concertina wire and military vehicles. I have arrived at Camp Ripley, the desolate forward operating base of the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU). From here Alabaman Col. Kenneth McKenzie Jr., the 22nd MEU’s commander, has been directing 2000 Marines, and recently Army infantry troops as well, in combat operations against Taliban and other forces across an area half the size of North Carolina.

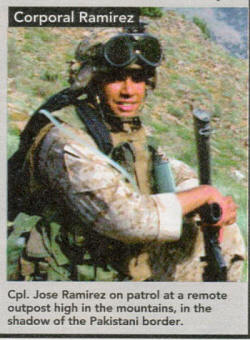

I have come to Afghanistan to observe the 22nd MEU and other Marine Corps units fighting in this often-neglected theater. My son Jim, with me as my photographer, is also carrying a message for Marine Cpl. Jose Ramirez, whom we are determined to locate during our visit.

At Bagram: A lesson in history

Two days earlier, we had left Ramstein Air Base in Germany, a busy hub linking medevacs and cargo to Iraq and Afghanistan. During a seven-hour flight, we sat on canvas jump seats and napped on the metal floor of an Air Force C-17 loaded with fresh cargo and finally landed at the main American base at Bagram.

Two days earlier, we had left Ramstein Air Base in Germany, a busy hub linking medevacs and cargo to Iraq and Afghanistan. During a seven-hour flight, we sat on canvas jump seats and napped on the metal floor of an Air Force C-17 loaded with fresh cargo and finally landed at the main American base at Bagram.

Built up by the Soviets during their ill-fated occupation of the country, Bagram is a lesson in history and of the contrasts in living styles that attend all wars. Its perimeter is littered with old Soviet weaponry and crisscrossed with still-active minefields.

We slept in an odorous, dusty room that was once part of a Soviet-built hospital. All around us, the American military-plus soldiers from at least a dozen other nations and hundreds of civilian workers -live in a world almost surreal in its contradictions.

Britney Spears, pizza and weapons

Bagram, home to more than 6000 soldiers, offers up the heat and isolation of a war zone and at the same time emits an unreality that might be found in an episode of M*A*S*H. The base has never been attacked other than by occasional rocket fire from distant mountains, but every person in military uniform carries a loaded weapon, even when walking to the base exchange or the day spa or pizza parlor. At the transient quarters, a visiting Army general even straps a shoulder-holstered pistol over his undershirt as he travels from his bedroom to the latrine one floor below.

Bagram, home to more than 6000 soldiers, offers up the heat and isolation of a war zone and at the same time emits an unreality that might be found in an episode of M*A*S*H. The base has never been attacked other than by occasional rocket fire from distant mountains, but every person in military uniform carries a loaded weapon, even when walking to the base exchange or the day spa or pizza parlor. At the transient quarters, a visiting Army general even straps a shoulder-holstered pistol over his undershirt as he travels from his bedroom to the latrine one floor below.

And yet, throughout the day, hundreds of soldiers in official Army gym clothes jog on Bagram’s roads and sidewalks, weaponless and worry-free. Just outside the Internet cafe, I watch an aerobics class where dozens of solemn-faced soldiers kick up their knees in unison, step-dancing to the rhythm of Britney Spears.

Unarmed, full-bellied civilians with thick Southern accents dish out food in the chow halls, run the laundry and operate supply trucks, compliments of Vice President Cheney’s ever-present Halliburton Co., which even announces when you sign onto the Internet that it has provided the connection.

A place of wind and dust

Camp Ripley offers neither the distractions nor the contradictions of Bagram. It is a place of wind and dust, sitting on an arid, empty plateau. The seriousness of the Marines’ mission permeates the air. At night the camp is eerily quiet and the darkness is nearly complete, interrupted only by green chem sticks marking pathways through the concertina wire and an occasional blue-lensed flashlight.

Camp Ripley offers neither the distractions nor the contradictions of Bagram. It is a place of wind and dust, sitting on an arid, empty plateau. The seriousness of the Marines’ mission permeates the air. At night the camp is eerily quiet and the darkness is nearly complete, interrupted only by green chem sticks marking pathways through the concertina wire and an occasional blue-lensed flashlight.

Struggling in the thick dust, we carry our gear from the airstrip to the small group of tents that mark Colonel McKenzie’s command post. Iron gray Sgt. Maj. George Mason sits at a small table in the darkness, smoking a cigar as he converses in a near-whisper with another Marine. Rising to greet us, the New Jersey-born Mason hands us thin mats and gestures toward two nearby one-man pup tents, where we will stow our gear and sleep on the ground. There is not one cot in the hundreds of tents that dot Camp Ripley’s moonscape. Colonel McKenzie and Sergeant Major Mason are testimony that the Marine Corps leads by example, sleeping on the dust-filled deck inside their own pup tents, no differently from the rest of their Marines.

The command operations center is a low-lit tent jammed with sophisticated computers. I learn that a recently arrived Army unit is in contact with guerrillas in the mountains to the east, not far from where the 22nd MEU’s Marines recently killed more than 100 enemy, including at least one Chechen. This largely unreported operation, the most extensive in Afghanistan in more than two years, has been overshadowed by events in Iraq and represents the farthest inland penetration by ship-borne amphibious forces in the history of the Marine Corps.

To an outpost in the hills

The next morning, we board a helicopter and fly north over vast reaches of desert, banking through sharp mountain passes. Gunships ride our flanks. A second helicopter follows in our trace. Bare scrapes of road mark the desert floor and the edges of many mountains.

The next morning, we board a helicopter and fly north over vast reaches of desert, banking through sharp mountain passes. Gunships ride our flanks. A second helicopter follows in our trace. Bare scrapes of road mark the desert floor and the edges of many mountains.

Every now and then, we see a lone vehicle, a herd of goats, even wild camels. Occasionally there are squares of mud walls, denoting an Afghan housing compound. Finally we fly past a half-dozen Marines manning a hilltop outpost, and on the other side we descend toward a streambed at the edge of a village. Green smoke from a grenade curls into the air, marking the landing zone. And in minutes, we are at the command post of “One-Six” – the 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment.

One-Six is now in its 74th consecutive day of offensive combat operations. Led by Pakistani born Lt. Col. Asad Khan, whose call sign, appropriately, is “Genghis,” and a particularly daring sergeant major, Kentuckian Thomas Hall, the three 200-man rifle companies have covered enormous distances along the rough roads and narrow mountain passes. Early on, the Taliban attempted a series of three-point, V-shaped ambushes and learned a costly lesson. Rather than going on the defensive once ambushed, the Marines attacked in classic fashion, stunning the ambushers and chasing them down one by one.

A five-vehicle convoy picks us up, along with several bags of precious mail brought in by the helicopters. It is brutal hot in the Humvees as we drive along craggy mountain roads. Dust pours into the open windows, mixing with the odor of the fuel cans behind us. On the roofs of the Humvees, gunners stand watch, dark goggles on their eyes, their boots fixed into canvas straps that descend into the center of the cab.

The square mud housing compounds seem to blend into the desert as we pass. Young children stare curiously, a few daring to wave. A vehicle breaks down, and we leave it behind with another one for security. It is a risky but daily occurrence, with the Marines stretched out so far and wide.

The tip of the spear

Charlie Company, along with several dozen Afghan soldiers, is set up at the edge of a swiftly flowing river, its vehicles marking the edges of the patrol base. On the far side of the river, a group of villagers has gathered to watch, and a smaller group of nomads has set up its own tents. We have reached the very tip of the spear whose hilt began in Bagram, and these Marines have an edge to them. They are well-disciplined but cocky, the series of recent firefights having cost them few casualties. At the same time, they are weary, knowing they are toward the end of their deployment and soon will be heading home.

Charlie Company, along with several dozen Afghan soldiers, is set up at the edge of a swiftly flowing river, its vehicles marking the edges of the patrol base. On the far side of the river, a group of villagers has gathered to watch, and a smaller group of nomads has set up its own tents. We have reached the very tip of the spear whose hilt began in Bagram, and these Marines have an edge to them. They are well-disciplined but cocky, the series of recent firefights having cost them few casualties. At the same time, they are weary, knowing they are toward the end of their deployment and soon will be heading home.

That afternoon we wade the chest-deep river, moving quickly through a large portion of the village on the other side as the Marines cordon and search different compounds, looking for Taliban and stashed weapons. It is intricate, exhausting work that will carry over into the next day and the next in other remote villages. Dogs are barking and snarling. Bearded men are protesting. Women with long memories of abuse during the Soviet occupation are hiding with their female children. A few gritty female Marines are attached to the company in order to search the women without insulting local traditions. Afghan interpreters conduct in-depth interrogations under the direction of Marine counterintelligence. Four-man fire teams work with quick precision, tempers occasionally flaring from the tension and the heat, searching room after room, compound after compound, then marking large X’s on the mud doorways with their bayonets. Opium and marijuana are omnipresent, drawing frequent jeers from Marines who must deal with stoned-out Afghans but who are not allowed even to drink a beer inside this country for fear of offending Muslim sensibilities.

Then it is over, and we wade back across the river. At night I lay amid the smooth round stones of the riverbank. My clothes are still wet from the patrol. A soft, cooling wind rises off the river, and I pull my flak jacket up to my chin as if it were a blanket. The sky is brittle clear and the stars shine with amazing clarity. As I lay on my back, I see a satellite slowly crossing the sky. And I wonder if it is watching us.

A last distant outpost

Kilo Company of the 3rd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment is far to the north of Camp Ripley, strung out along a series of remote platoon outposts that look directly at the Pakistani border. We find Kilo’s third platoon at a Special Forces camp high above a gorgeous river, looking down at a valley so green that it could be in Vietnam. In this odd war that combines so many aspects of national security, it is no small irony that vast fields of opium sprawl in plain view just on the other side of the river.

Kilo Company of the 3rd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment is far to the north of Camp Ripley, strung out along a series of remote platoon outposts that look directly at the Pakistani border. We find Kilo’s third platoon at a Special Forces camp high above a gorgeous river, looking down at a valley so green that it could be in Vietnam. In this odd war that combines so many aspects of national security, it is no small irony that vast fields of opium sprawl in plain view just on the other side of the river.

The Marines’ work up here is different-defensive rather than offensive, with Kilo’s platoons under the operational control of the Army’s Special Forces. For eight days at a time, combined squads of Marines and Afghans man dangerous outposts on top of nearby mountains that are reachable only by helicopter. Daily squad-sized security patrols trace the hills overlooking the main compound. In the cave-pocked valleys along the border, small Special Operations teams are frequently inserted by helicopter, conducting long range patrols in search of al-Qaeda and other terrorists’ base camps.

To reach this distant outpost, we hitch a ride in an Army CH-47 Chinook helicopter whose missions for the day include delivering resupply loads. As we fly, Apache helicopters constantly cover our flanks. The many-houred journey from Bagram is routine for these highly skilled pilots, who on the trip must negotiate a foglike sandstorm through hazardous mountain passes and drop off large loads by hovering at the edge of sharp terrain that leaves no room for error.

Journey’s end

And here, in the shadow of the Pakistani border at the far edge of Afghanistan, we finally link up with Corporal Ramirez. Dripping sweat, he breaks from a working party when our helicopter arrives, greeting Jim and me with a handshake and a quick embrace before getting back to work. My son later joins his squad on a combat patrol up into the steep mountains. Then, as night falls, we talk for more than an hour of home and of Afghanistan. The seductive quiet of the mountains, where al-Qaeda’s forces watch, listen and hide, can be deceptive. Shortly before our arrival, a three-man patrol repeated an earlier route and was quickly wiped out as it stepped down a ridgeline into a ravine. The platoon is still haunted by the bravery of the patrol’s radio operator, a 19-year-old Tennessean who fought the attackers to his death, giving up his radio only when they cracked his forearm on a rock to pry it out of his hand.

And here, in the shadow of the Pakistani border at the far edge of Afghanistan, we finally link up with Corporal Ramirez. Dripping sweat, he breaks from a working party when our helicopter arrives, greeting Jim and me with a handshake and a quick embrace before getting back to work. My son later joins his squad on a combat patrol up into the steep mountains. Then, as night falls, we talk for more than an hour of home and of Afghanistan. The seductive quiet of the mountains, where al-Qaeda’s forces watch, listen and hide, can be deceptive. Shortly before our arrival, a three-man patrol repeated an earlier route and was quickly wiped out as it stepped down a ridgeline into a ravine. The platoon is still haunted by the bravery of the patrol’s radio operator, a 19-year-old Tennessean who fought the attackers to his death, giving up his radio only when they cracked his forearm on a rock to pry it out of his hand.

The message for Corporal Ramirez, carried so many thousands of miles by my son, is a letter from my daughter, Sarah. I have no need to read it to know the gist of what she said. This is the second time that Corporal Ramirez has deployed to Afghanistan in little more than a year. I have seen her struggle with the pain of these separations – forgoing normal college rituals, forcing herself to learn more about this proud oddity called the Marine Corps and this remote country that has the potential to so drastically alter her life. I have listened on the phone as her calmness descended into sudden tears when asking about news of casualties. Two days before my trip, I watched her celebrate her 21st birthday, an evening of forced gaiety with one glaring, remembered absence.

And yet, saying good-bye to Jose the next morning as a Black Hawk helicopter swoops in to take us back to Bagram, I know something else – that he and I, and so many others, cannot allow ourselves to feel unique in these emotions. Indeed, they are being repeated a hundred thousand rimes over, every day, among those who have been sent into harm’s way. My only wish is that the rest of America might somehow comprehend their depth and their intensity.