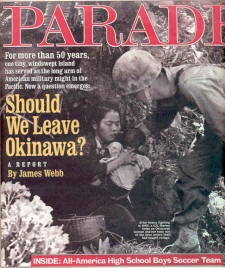

Foreign Policy & National Security

Should We Leave Okinawa

March 11, 2001

by James Webb, Parade Magazine

Amid calls for American troops to go home, a decorated Marine and ex-Navy Secretary examines whether we can afford to give up our most important military outpost in the Pacific.

Amid calls for American troops to go home, a decorated Marine and ex-Navy Secretary examines whether we can afford to give up our most important military outpost in the Pacific.

Contributing Editor James Webb was Secretary of the Navy under President Reagan. Earlier, he received the Navy Cross and Silver Star for his service as a Marine in Vietnam. In January, Webb made his latest of many visits to Okinawa for PARADE. His mission: to explore the implications of removing US forces from the island known to generations of GIs as “The Rock.”

The first time I ever saw Okinawa, in 1969, I arrived at Kadena Air force Base on a military charter from California, by way of Hawaii and Wake Island. Military buses shuttled us past fields of sugarcane and small, windswept towns rebuilt in the quarter-century since the island had been flattened in World War II’s costliest Pacific battle. Like most of the 400,000 Marines who went to Vietnam, I was “processed” at Camp Hansen. Back then, the camp was an ocean of adrenaline. Racial tensions among Americans were high. Kin, a village just outside the camp, was filled with bars and strip joints. The air was charged with the promise of violence from Marines on their way into or out of a war that would claim 100,000 casualties for their Corps.

Today, Okinawa is far more staid. Many of the 19,000 Marines stationed there-and most of the 10,000 Air Force, Navy and Army forces-are on three-year tours with their families. The raucous barracks of the past have largely been replaced by apartment towers. Much of the training takes place “off-island.” Sensitivity to Okinawan civilians is extreme. (Just last month, for example, the chief of U.S. forces on the island publicly apologized for a leaked e-mail in which he called Okinawan officials “wimps.”) Bars and clubs still exist, but the tone is subdued. America, once an occupier, has become a tolerated guest.

Still, tensions between Okinawans and Americans can erupt. When a Japanese court found that three GIs were involved in the rape of an Okinawan girl in 1995, the island’s then-governor, Masahide Ota, led protests demanding an American withdrawal. (Cooler heads prevailed, and Ota, who ran on the issue in 1998, was not reelected.) But even without such tensions, there have been serious calls in both America and Japan in recent years for the bases to be removed. Some claim U.S. forces there have outlived their strategic relevance. Others say that the island, whose population has, tripled to 1.1 mil lion since World War II, has outgrown the bases and needs to modernize its economy and reclaim its heritage.

I have been to Okinawa many times since my first stop there on the way to war. On my most recent visit, in January,

I returned with one important question: What are the true implications of a U.S. pullout, not only for American interests in East Asia but also for Okinawa?

Unlike the rest of Japan, Okinawa has mingled with foreigners for centuries. Okinawans are not considered “ethnic” Japanese, either in Japan or among themselves. The Ryukyu Islands, to which Okinawa belongs, were annexed by Japan in 1879; before then, Okinawans paid tribute to both Chinese and Japanese warlords. From 1945 until 1972, the island was a U.S. protectorate, and even today it hosts the majority of all GIs in Japan.

Among those who believe the U.S. should remain strong in the Pacific, there is little argument that Okinawa–350 miles from Taipei, 700 from Seoul, 800 from Manila and about 1500 from Singapore-is ideally situated not only for the defense of Japan but also for rapid deployment to a wide array of potential crises. Annually, Marines from Okinawa participate in about 70 training exercises throughout the Pacific Rim, plus humanitarian missions to locations such as Bangladesh and East Timor. If war were to break out anywhere in that vast region, they would be among the first to go.

Ironically, some U.S. defense planners believe that the limits American forces have placed on themselves in order to satisfy the Okinawan people are too restrictive, leading them to recommend a substantial withdrawal from the island.

Last October, a much-publicized study sponsored by the National Defense University recommended a “diversification throughout the Asia-Pacific region” of U.S. forces on Okinawa. And former Japanese Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto, now minister for Okinawan affairs, speaks often of “the suffering of the Okinawan people” as a result of the American bases, implicitly supporting their removal.

Last October, a much-publicized study sponsored by the National Defense University recommended a “diversification throughout the Asia-Pacific region” of U.S. forces on Okinawa. And former Japanese Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto, now minister for Okinawan affairs, speaks often of “the suffering of the Okinawan people” as a result of the American bases, implicitly supporting their removal.

Supporters of withdrawal are vague about where these “diversified” forces would be based. Some invoke the politically volatile Philippines, where U.S. bases existed until 1992. Others hint at already crowded Guam or the sparsely populated Northern Marianas. Some say Singapore or even Vietnam. But, in my view, it’s important to make a distinction between sending units based on Okinawa to train in other countries and relocating them permanently. The volatile Pacific of today demands that U.S. forces be consolidated. Yet most diversification scenarios would put more of our forces at risk by scattering them among countries where the governments are not as stable. “The only locations without such political risks are Australia and Hawaii,” notes Dr. Mackubin T. Owens, a professor of strategy at the Naval War College.

And there is another consideration: It is far from clear that the Okinawans really want us to leave.

Perhaps the greatest change of the past 55 years has been the subtle merging of two cultures. Despite periodic friction, “Okinawans have come to understand the Americans and the presence of the bases,” says the noted Okinawan historian Kurayoshi Takara.

Yasumitsu Tsuha, a community leader and participant in negotiations to relocate an air facility near his town of Ginowan, affirms Takara’s observation: “The period before reversion to Japan allowed us to reconsider our own historical uniqueness as Okinawans. At the same time, we came to know the Americans and to admire their culture.” Many Okinawans term their willingness to adapt to outside influences as champura bunko- “stir-fried culture.”

Okinawans who oppose US bases do so for varying reasons. Some are concerned about militarism. Others know controversy tends to increase the generous payments made to those who lease the land on which the bases are set. Finally, there’s an activist coalition of Japanese trade unionists, Communists and Social Democrats dedicated to removing both the bases and American influence from Okinawa. This faction backed former governor Ota, whose often-expressed goal was “a peaceful, military-free Okinawa.”

Okinawans who oppose US bases do so for varying reasons. Some are concerned about militarism. Others know controversy tends to increase the generous payments made to those who lease the land on which the bases are set. Finally, there’s an activist coalition of Japanese trade unionists, Communists and Social Democrats dedicated to removing both the bases and American influence from Okinawa. This faction backed former governor Ota, whose often-expressed goal was “a peaceful, military-free Okinawa.”

Retired Marine Col. Gary Anderson spent seven years on Okinawa and commanded Camp Hansen for two. Recalling the 1995 rape, he told me: “Ota is deft at manipulating public opinion, and he cynically turned the incident into a national crisis.” Condemning the incidents, Anderson nonetheless argues for a sense of proportion: “Virtually every community in the U.S. would welcome a crime rate as low as that for our servicemen on Okinawa.”

Indeed, serious crime by Americans has dropped 78% in the last 10 years, and a recent poll indicated that 74% of Okinawans have a favorable opinion of the U.S. While most would prefer reduction in the bases, only 16% believe all Americans should leave. Okinawans also understand the economic benefit Americans bring to their island, poorest of Japan’s 47 prefectures: about $1.2 billion a year, or roughly $1000 for every Okinawan. “Because of the [Second World] War, Okinawans are extremely uncomfortable with militarism,” says the historian Takara. “But this is not necessarily directed at America itself.”

The removal of U.S. bases also would have implications for a resurgent China. Okinawa’s relations with that country go back more than 500 years, and many Okinawans are proud of such ties. In recent decades, the Chinese have played upon Okinawan goodwill, and there is little doubt that if U.S. bases were removed, China would attempt to extend its influence over Okinawa, which is nearer to Taipei than Tokyo. Lately, China has shown an insistent tendency to confront Japan. Chinese military vessels made at least 17 incursions into Japanese waters last year. In addition, China still claims Japan’s Senkaku Islands, lying between Taiwan and Okinawa. And China has never accepted Okinawa’s 1972 reversion to Japan.

The removal of U.S. bases also would have implications for a resurgent China. Okinawa’s relations with that country go back more than 500 years, and many Okinawans are proud of such ties. In recent decades, the Chinese have played upon Okinawan goodwill, and there is little doubt that if U.S. bases were removed, China would attempt to extend its influence over Okinawa, which is nearer to Taipei than Tokyo. Lately, China has shown an insistent tendency to confront Japan. Chinese military vessels made at least 17 incursions into Japanese waters last year. In addition, China still claims Japan’s Senkaku Islands, lying between Taiwan and Okinawa. And China has never accepted Okinawa’s 1972 reversion to Japan.

Military bases bring liabilities as well as benefits- whether in Hawaii, home to more than 41,000 troops, or on Okinawa. But few can dispute the important contribution made to regional stability by cooperation between the U.S. military and the Okinawan people. Now is not the time to trade the known-Okinawa-for new difficulties in other countries, or for the U.S. to reduce its presence in Asia in the face of an invigorated Chinese military. A wiser course, I believe, would be to continue recent efforts to restructure the bases on Okinawa in a way that is compatible with the island’s future. Fundamental to that is a better articulation of our reasons for staying on.

“Okinawans accept the bases,” notes Kurayoshi Takara, “but it is still hard for many to understand their importance. The U.S. always allowed the Japanese to explain the importance of American troops, but the Japanese usually deal with the issue through avoidance. The U.S. needs to explain.”

Indeed it does – both in Japan and here at home.