Military & Veterans

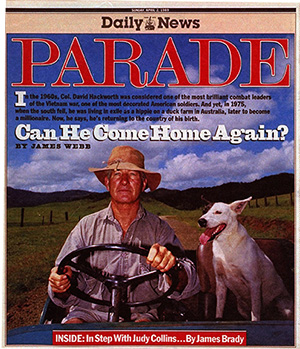

Can He Come Home Again?

April 2, 1989

by James Webb, Parade Magazine

David Hackworth’s love for the Army was greater than anything else in his life. Until it disappointed him.

David Hackworth’s love for the Army was greater than anything else in his life. Until it disappointed him.

Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, is an historic post, made famous in the novel From Here to Eternity. One almost searches for the rowdy, khaki-clad soldiers of yesteryear as he passes the quiet streets and stately old parade ground. But those men are gone now, replaced by young soldiers in baggy camouflage fatigues.

A warrior from an earlier time watches these young inheritors. He wears a powder-blue shirt and tan slacks. Both arms are scarred from combat wounds and surgically removed tattoos. His hair is gray and his eyes, the color of his shirt, are merry and discerning. David Hackworth is back inside an Army post for the first time in 18 years.

“How much does this weapon weigh?” he asks a soldier carrying an automatic rifle, who peeks at a card for the answer. “How would you like to fire this weapon in combat?” he queries the gunner of an antitank rocket, who confesses that he has never even fired one in peacetime.

David Hackworth has not lost his keen eye, or his irreverence. And these soldiers could use his help, for he knows their trade like few others. But it isn’t that easy. To many, he is an albatross who carries with him the ghost of an Army that, in his view, failed itself and the nation by not winning the war in Vietnam. To others, he is simply a warrior who became an eccentric.

I had heard about “Hack” for years from Army veterans and from journalists who had covered the Vietnam war. His story had the grist of classic tragedy: the odds he overcame as a boy, his courage and dedication on the battlefields of Korea and Vietnam, the dreadful end of a brilliant career, the bitterness that drove him from his homeland to live in Australia, where he flourished as an entrepreneur. I heard that he had written a book and was finally coming home.

I felt a kinship with David Hackworth. During our interviews, we often stopped to trade stories from a war in which we had both bled. At the end, I gave him the most sincere tribute that one warrior can pay to another: I gladly would have fought alongside this man.

But there are problems with David Hackworth too.

He began the Vietnam war – as did the United States Army – with a dedication to discipline, a proven legacy of valor and a belief that the enemy could and should be soundly defeated. Hackworth spent four years on the battlefield, adding four Purple Hearts for wounds in action to the four he had received as a young soldier in Korea, and becoming perhaps the most decorated living American soldier. His combat exploits in both wars were the stuff of legend. He was awarded two Distinguished Service Crosses, second only to the Medal of Honor; nine Silver Stars, four Legions of Merit and eight Bronze Stars.

“Hack is the finest combat leader I have ever seen,” syas Brig. Gen. John Howard, a West Pointer who served under Hackworth as a platoon leader. “He had no peer. He simply had an innate sense of the battlefield.”

“Hack is the finest combat leader I have ever seen,” syas Brig. Gen. John Howard, a West Pointer who served under Hackworth as a platoon leader. “He had no peer. He simply had an innate sense of the battlefield.”

“He was the most inspirational leader I saw in 25 years of Army service,” notes Doug Holtz, who spent time as both an enlisted draftee and an officer.

Hackworth, now 58, was an almost certain promotee to general – an unimaginable feat for a man who had run away from an orphanage at age 14 and had largely educated himself after enlisting in the Army at age 15. He was known as an inspirational leader and a bold tactician. He was a respected thinker and writer, a protégé of the military historian S.L.A. Marshall and a favorite of former Army Secretary Stanley Resor.

And yet… By the time South Vietnam fell in 1975, David Hackworth was living in exile as a self-described “hippie” on a 160-acre farm he had built from scratch in the rain forests of northern Australia. He had stormily departed from Vietnam and the Army in 1971, after castigating the Army’s strategy and leadership in a TV interview on Issues and Answers and predicting with haunting accuracy in a Newsweek interview that “the North Vietnamese flag [will be] flying over Saigon in 1975.”

David Hackworth’s life plays on a big screen. It’s filled with great heroism and grand flaws. In many ways, his story is an allegory of the Army itself following World War II. His improbable successes seemed almost a magnification of the opportunities the Army provided; his disenchantment provided a harsh judgment of its foibles and travails. And his trek from spit-and-polish sergeant to spit-in-your-face colonel mirrored the Army’s long march from World War II victors to the humiliated, dispirited brigades that limped home from Vietnam.

“He was the very best we had,” remembers retired Lt. Gen. Hank Emerson, another legendary warrior who, like Hackworth, twice won the Distinguished Service Cross. “There is no soldier I respect more. He could do it all. He could write, speak, fight – you name it. He would have had at least three stars. And he came to a terrible end.”

At a time when other boys his age were trying to figure out what to say to that cute girl at the bus stop, David Hackworth was in the Merchant Marine, spending liberty calls in steamy Pacific ports and touring battlefields still littered with the debris of recent slaughter. A year later he joined the Army and was reporting to the 752nd Tank Battalion in Italy, a unit gone wild as its veterans waited to be shipped home from World War II. He then served as a squad leader in the elite Trieste United States Troops. Young Hackworth had no qualms about pushing his squad to perfection. He was so tough, and so thoroughly motivated, that his older squad members nicknamed him “Sergeant Combat.”

The name seemed to fit. From Trieste he volunteered for Korea, fighting from Pusan to the Yalu River and back again during the disastrous early days of the war. He stayed until the end, with time out only to complete the infantry officer’s course at Fort Benning, Ga., after receiving a battlefield commission at the age of 20. He finished the war with three Silver Stars, two Bronze Stars, four Purple Hearts, and a reputation for charismatic, independent leadership.

“The Army had become my home,” Hackworth says of those early years. “I loved it. I belonged there. And it remained my first and favored love for 25 years. I was a soldier 24 hours a day.”

Between wars, Hackworth educated himself. He became an astute thinker and a prolific writer on military tactics, the author of many challenging and thought-provoking articles. He was a favored co-author of military writer S.L.A. Marshall. He also wrote Vietnam Primer, one of the most important internal textbooks of the Vietnam war.

Hackworth spent more than four years in Vietnam, first with the 101st Airborne Division and then – after two years at the Pentagon – as a battalion commander with the 9th Infantry Division and with a number of Vietnamese units and advisory commands. His battlefield performance embellished his reputation as a bold, imaginative leader who savored independence of thought and action.

During this time at the Pentagon, Hackworth surveyed the progress of the war with increasing frustration at the Army’s lack of overall objectives and its failure to adapt its tactics to the enemy. He also was one of the earliest critics of “ticket-punching” – the policy that fed officers into the battlefield for a few months to give them some combat experience in order to “round out their resumés,” instead of focusing on leaders who could fight more effectively, stay longer and win the war. After the surprising Communist strength in the 1968 Tet Offensive, he wrote, “the Army has botched the war… To win we need a Wingate, Giap, Rommel, Jackson, McNair-type soldier. But I doubt if our present system will produce such an individual.”

In a memorandum to Gen. William Westmoreland, Hackworth elaborated: “The capable combat leader has traits which are inconsistent with today’s criteria for high-level positions. As a result, men who know how to win in battle, with rare exception, just don’t get ahead.” He later wrote that ticket-punching was the Army’s “death blow,” a response to demands from top civilian leaders for “officers who would not only command fighting men but also teach physics, serve as statesmen and advise industry. This produced officers conversant in many matters, and proficient in very few.”

Discouraged by the failure of the Army to adjust to the war, Hackworth contemplated resigning but instead volunteered to return in command of a battalion of ill-motivated draftees. “I was obsessed with winning,” he explains. “I believed that it was more a question of leadership than of doctrine, that if I could take draftees and make them win, I could show the Army how to turn the war around.”

In January 1969, he took over a battalion in the 39th Infantry Brigade that had failed to account for a single enemy casualty in six months and yet had lost more than 500 killed or wounded. “It was total disintegration,” he comments. “It wasn’t even a military organization.”

Hackworth shaped up the battalion in less than a month. By emphasizing surprise, deception, mobility and imagination – and by rotating platoons to the division rear for unit training – he turned the “hard-luck” battalion into the “hardcore” battalion. In five months, it accounted for more than 2700 enemy dead, with a loss of only 26 soldiers.

Hackworth (L) poses with fellow soldiers after 1966 battle for village of My Cahn: U.S. claimed victory, he says, but suffered heavy casulaties.

Despite his successes, Hackworth laments that there was no interest in his revolutionary tactics. “There were seven general officers in my chain of command, and not one of them even asked me how it worked,” he recalls. “I wrote extensive reports on how we could win and still preserve our human assets. At the same time, my old division – the 101st – was repeating the mistakes of the past, making 11 assaults up Hamburger Hill, losing almost 400 casualties, only to abandon the hill a few days later. The Army was pushing ticket-punchers through Vietnam like tourists: Spend a few months in combat, get your Combat Infantryman’s Badge, go home and wait for the final pullout.”

If Hackworth had gone home in 1969, he would have had an unmatchable chest-full of medals, a reputation as one of the finest mid-level combat commanders in Army history and a bright future. Instead, he stayed on in Vietnam and grew more bitter and outspoken. He twice refused orders to attend War College, opting to work with the South Vietnamese. “Vietnamization” was in full swing, and he quickly decided it was a doomed effort. “The ARVNs were good soldiers,” he remembers, “And they had some great leaders at the top. But their mid-level leadership was a disaster. Too many were political appointees who were more concerned about stealing than fighting. They betrayed their nation and their soldiers.”

It was clear to him by 1971 that the war was lost. “It was like a play,” he says, “and it was time to bring the curtain down. Our top leaders lacked the guts either to fight the war right or to offer their resignations in order to stop it. I didn’t want anyone else to die when the purpose had gone. We still could have won, even in 1971, by placing mid-level ARVN units under the direct command of American officers and rebuilding the South Vietnamese officer corps. But that wasn’t going to happen.”

Hackworth, never a “by-the-book” soldier, rebelled. Embittered by what he viewed as a paralysis in Army leadership whose end result was an acquiescence to continued American casualties, he decided to “hurt the Army as badly as she’d hurt me,” as he puts it. “I went out of my way to break every regulation I could. I took immense joy in screwing the system, joy that was only matched by the fact that in the process my men had some of the best times of their lives.” The man who, as a young sergeant, had marched his squad to the front gate in Trieste to warn them that there would be no liberty without military perfection in the barracks and who, as a battalion commander in 1969, had relieved a radio operator for having written an expletive directed at the Army on his helmet, now led an antidisciplinary assault.

His remote command post deteriorated into what he terms “one big broken regulation.” An Inspector General team descended on his command after his Issues and Answers diatribe, finding massive violations. He had erected a massage parlor that doubled as a house of ill repute inside his compound. He had gambled with subordinates. He had begun a “drug amnesty” program, with a buddy system that, if all else failed, allowed the “clean” buddy to urinate in place of the drug offender, avoiding court-martial and allowing him to “go home, hopefully to start a better life.” He was accused of currency violations and subjected to a seven-year audit of his tax records. And it was only after being represented by Joseph Califano, later HEW Secretary, and Brendan Sullivan, whose most recent military client has been Oliver North, that Hackworth could retire without being court-martialed.

S.L.A. Marshall wrote that Hackworth, while a “true hero,” was “overlong in battle and emotionally imbalanced,” adding that he was “out of his depths” in discussing the strategy of the war. Hank Emerson, who in 1977 retired after criticizing the ill-fated Bradley fighting vehicle, agrees that Hackworth was “burnt out” and laments that Hackworth’s superiors did not send him home earlier.

“He was our treasured star,” says Emerson. “We needed him during the years just after the war.”

It is human maxim, as old as Achilles, that those who give the most often end up paying the biggest price. In war, some inevitably die. But in long, inconclusive wars, others suffer the death of their spirit, brought on by the paradox of their repeated courage, on the one hand, and the overwhelming futility of their effort, on the other. And so David Hackworth, eight times wounded in two such conflicts, ceased to be a soldier in a war he believed was winnable long after he’d ceased to believe it would ever be won.

As Gen. John Howard put it: “It has been said that David Hackworth ‘died’ in the service of his country in 1971.”

Now, after 20 years abroad, Hackworth is coming home. The hippie phase is long gone, having given way to entrepreneurship. Today, he is a millionaire “a few times over” from the management of a restaurant business and from a duck farm begun with 12 ducks that soon was selling 2000 ducks a week.

In Australia, his bitterness manifested itself in outbursts given to rhetorical extremes. He became deeply involved in the anti-nuclear movement. He warned that the Carter Administration’s reaction to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan might somehow bring us into another Vietnam. In 1981, he stated that Ronald Reagan “had surrounded himself with a bunch of Nuke the Pukers” and began stockpiling food and water at his farm in case of nuclear war. He blames U.S. policy for having “sent Castro into the Soviet camp” and having “turned Central America into a killing field.” He writes in his new book, About Face, that successive administrations have “allowed the CIA to run riot in Third World nations, with excesses that rival the Nazis.”

And yet, in person, he seems to have vented a great deal of his earlier anger. “As I wrote the book, the bitterness went away,” he says. “I was so affected by Vietnam. The book gave me the catharsis I had needed for all these years.”

Hackworth plans to move to Colorado and hopes to become a military commentator. “My first love has always been the Army,” he says. “I think I have some important insights to offer, especially in the area of readiness and training.”

And we have much to learn from David Hackworth – about personal courage, human resilience and what it takes to train and lead combat soldiers. But he also stands to learn a great deal from this nation he left 20 years ago – about its continuing obligation to lead the free world and how we slowly but honestly have been coming to grips with our national failure in Southeast Asia.

And perhaps we can relearn together the lesson of tolerance. We all burned out in some fashion toward the end of the Vietnam war. But beyond that anger and disappointment, there are hands to shake and wounds that yet may heal.