Articles by Jim

Help for the Forgotten

March 25 1990

By James Webb

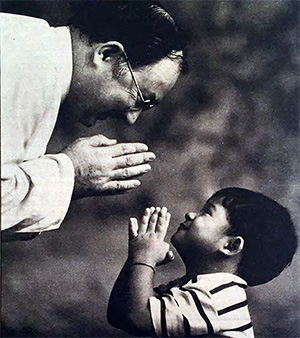

In Bangkok’s worst slums, Father Joe Maier makes sure there is help for the Forgotten

In Bangkok’s worst slums, Father Joe Maier makes sure there is help for the Forgotten

Imagine a nation where almost any act is permitted as long as it does not infringe upon another person’s freedoms; a country that knows no racial prejudices; a country that prospers while other nations in its region are wracked by war and famine, whose economy grows at nearly 11 percent a year, among the highest rates in the world.

Over this nation superimpose another, where thousands of the crippled and blind sit listlessly on sidewalks throughout the day, marketing their tragedies as smartly as vendor in nearby stalls market their T-shirts.

Both nations are Thailand, the ancient kingdom in Southeast Asia. Unlike its neighbors – Burma, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam – Thailand has prospered greatly in recent times. Having few rules governing human conduct, Thailand has become a magnet for investors, businessmen and entrepreneurs – many of them Americans. Some have done well indeed in this nation where each individual is left to succeed – or fail – on his own.

And some come for other reasons. Father Joe Maier, who grew up in Longview, Wash., has dedicated his life to the Thailand of the unsuccessful, the poor, the seemingly forgotten.

“We do the work that the government can’t or won’t do,” says Father Joe, who has been ministering to the people of Bangkok’s worst slums for 18 years. As tourists from the West languish in the tropical heat on the veranda at the luxurious Oriental Hotel or take limousine trips down to the glittering, sensuous frolic of Pattaya Beach, Father Joe makes his rounds inside the Slaughterhouse section of Klong Touey, a neighborhood devastated by poverty, drugs and disease. “Someday, the government will find the resources and the inclination to take care of these people,” Father Joe says. “We try to speed that process.”

Every night, 3000 hogs are butchered in the slaughterhouse. The laborers’ wives and children try to sleep nearby – in some cases only a few feet above the odorous concrete pens – as hogs shriek and workers chatter and scream. There is no refrigeration, so the work must be done at night, the delivery trucks on their way before dawn. Since Buddhists have an aversion to killing animals, much of the slaughterhouse work is done by Catholics, whose 112 families are the core, although not the totality, of Father Joe’s ministry.

One morning, I walk with Father Joe along the ramshackle houses made of plywood and loose sheets of tin. The stench is everywhere: from the hog pens, from the hogs themselves, from the stagnant pools of water left by the slaughter of the night before, from the piles of dog manure at our feet and from the Chao Phya River, which is so polluted where it passes Klong Touey that the bacteria count recently was measured as nine times higher than that in human excrement.

Hogs – many weighing several hundred pounds – arrive throughout the afternoon in open trucks. They squeal and cower. In one pen, a muscular young man with tattoos on his thighs carves up a hog that has died early from the heat.

Clutches of people sit in outdoor stalls, some numb from opium, others merely enduring the heat. Most of them greet Father Joe warmly when they see him, folding their hands together underneath their chins in the Buddhist “Y.” Father Joe returns their gestures and speaks to them in fluent Thai. Nearby, children and dogs play listlessly in the dirt.

In one small, open-air home, and old woman – she’s 103, says Father Joe – bargains with him over some goods he is buying from her. Inside her shack, a kitten sleeps next to a dozing rabbit, and a gray ferret slitters in and out of the raised boards that make up the floor. A shirtless man walks toward us across a mud pathway. His muscles are hard from his work, but his face is devastated with wrinkles. His eyes are so red, they appear to be burned by fire. He picks up his naked baby son and lovingly kisses him.

We enter a tiny store that stands a few feet from a slaughter pen. The wall nearest the pens has been knocked out, and young men are shoveling away the muck where a gutter carrying cooling water from the river has become clogged. The muck smells worse than sewage. On one wall is a shrine to Jesus, similar to a Buddhist shrine, with flowers and joss sticks below the picture. Unbelievably, in the midst of the squalor, two small children stand before a color television playing the same Nintendo game my own kids play in our basement at home.

Father Joe came to Thailand in 1967 as a Redemptorist missionary priest, spent three years in an outlying province and another year working under primitive conditions with villagers in Laos. In 1971, he moved to Bangkok, setting up a ministry without walls inside the city’s worst slums. Today, he is a fixture among the approximately 65,000 people of these slums. American expatriates there alternately call him “a Bing Crosby with guts” and “the Mother Teresa of Thailand.”

To continue his ministry, he depends on donations to his umbrella organization, the Human Development Center. His achievements could make any Congress blush with envy. Starting “from scratch,” he has established 25 schools, extensive sports activities that tend to the recreational needs of 4000 children, a medical clinic with a caseload of 20,000 people a year, a boys’ home, a girls’ home and a self-supporting sewing project that employs more than 200 women and sells goods in Thailand and nine foreign countries. He works with prison inmates, particularly in the area of drug-related crime, and is an internationally recognized expert on drug rehabilitation and prison reform. Recently, his center resettled 1000 families evicted from other slums.

I ask Father Joe how a Catholic can minister to a community that is 98 percent Buddhist. “You teach what you are,” he says. “I exude Christian calmness. There is humor and wisdom in Christ, and the people see it through me. The Buddhist life and the Christian should be dedicated to getting rid of the anger in your heart. I see much more as I enter my dotage, surrounded by violence. I’m not into making converts. I’m into teaching Buddhists be good Buddhists and Catholics be good Catholics.”

Not long ago, Father Joe witnessed a murder. The police wanted him to identify the killer, but he refused. “I showed them the bullet casings,” he says. “I told them there were other witnesses. I told them they could not ask me to take part in their legal process. I am not a catcher of thieves and killers. I am a priest.”

Later that day I walk downtown. At one corner, a new hotel is being built in the place of an old one. Next to the site, 100 well-dressed Thais stand at a gleaming Brahmin shrine. Someone, probably a family, has hired musicians and dancers. Exotic music emanates from a large wooden instrument that resembles a xylophone. Four women in ornate costumes perform an ancient dance, their limbs twisting with the music. People place gifts at the feet of the shrine. It is garlanded with leis of fresh flowers. Soon it will stand next to a Grand Hyatt.

On the construction site, steel girders look like empty, tangled limbs where they stick out from the concrete. Workers cover the buildings like ants, making up for a lack of sophisticated machinery with their sheer numbers.

On the sidewalk outside the shrine, an old woman sits with a boy on her lap. His legs are twisted and useless. He is emaciated, waiting to die. A cup sits in front of them. A coin falls into it, and the woman presses her hands together in the Buddhist “Y,” a gesture of thanks. Then she stoically returns to picking lice out of the dying boy’s hair.

Watching all of this, I think of the Americans I’ve met and the work they are doing in this gentle yet dynamic country. Some would say this is heaven compared with Vietnam or Cambodia. Others might marvel at the harmony. A few might comment on the passing of the old hotel or celebrate the potential of the new one. But Father Joe would minister to the dying child and lament that his arms were not big enough to scoop up all the others and bring them to his clinic.

At that moment I think again of how much I admire his work and how embarrassed he seemed when I told him so. “You can’t get too serious out here,” he said. “Be cool.”