Articles by Jim

Dear Supe

July/August 1999

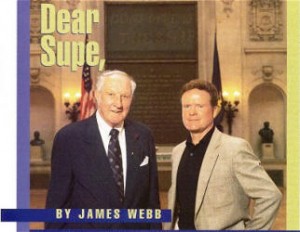

by James Webb, American Enterprise Institute

James Webb graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1968. For his service in Vietnam as a Marine Lieutenant he was awarded the Navy Cross, the Silver Star, two Bronze Stars, and two Purple Hearts. He went on to earn a law degree from Georgetown, then wrote several novels of war and military life, including one set at the Academy (A Sense of Honor). During the Reagan administration he served as Secretary of the Navy. His latest novel, The Emperor’s General, takes place in Douglas MacArthur’s Japan.

James Webb graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1968. For his service in Vietnam as a Marine Lieutenant he was awarded the Navy Cross, the Silver Star, two Bronze Stars, and two Purple Hearts. He went on to earn a law degree from Georgetown, then wrote several novels of war and military life, including one set at the Academy (A Sense of Honor). During the Reagan administration he served as Secretary of the Navy. His latest novel, The Emperor’s General, takes place in Douglas MacArthur’s Japan.

Below he offers the man who presided over his military education a few thoughts on what those hard days at Annapolis in the mid ’60s taught him.

MEMORANDUM

To: Rear Admiral C. S. Minter, USN (Ret’d); Former Superintendent, U.S. Naval Academy

From: Captain James H. Webb, Jr., USMC (Ret’d); U.S. Naval Academy class of 1968

Subj: After-action report

Sir:

This is in response to your letter of 12 May 1964, congratulating me on my acceptance to the Naval Academy and outlining my education and training should I report for duty as a midshipman. Please excuse the 35-year delay, but I did in fact report for duty, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that I have had a busy time of it ever since.

As you instructed, when I received your letter I gave it my close personal attention (italics yours), so that I might fully understand what would be required for me to commence a career in the United States Naval Services (italics yours), with the understanding that the Naval Academy exists for this purpose only (italics, you guessed it, yours).

That was a great letter, Admiral. It was honest, unapologetic, and immensely challenging. You might imagine the impact on a young man just past his eighteenth birthday to receive such a message, written by an admiral in the most powerful and well-led navy in the world, who like so many of his peers had cut his teeth in the dramatic and punishing arena of World War II. Reading about the struggles of that war had formed the template of my childhood. The theme song from Victory at Sea coursed through my brain as I opened the envelope. Film footage from great naval battles danced before my consciousness, as familiar to me as MTV music videos are to the children of today. I knew that you and others whom I might soon meet—and better yet, serve under—were at the forefront of the greatest battles in history.

And here arrived your letter, outlining the conditions under which I might be allowed to join you. I want you to know, even though you are long‑retired, that your blunt warnings motivated the living hell out of me. To be perfectly honest, they also scared the living hell out of me (italics mine). I doubt you had some Deputy Assistant Secretary of How To Make Nice peering over your shoulder as you wrote about what would be expected of me and my future classmates once we were “sworn in to the Naval Service and commenced a career.” If there had been such a Make Nice person in the Department of Defense in 1964, his or her authority would have ended somewhere between the E Ring of the Pentagon and the Marine guard at the Academy gate. For what do bow-tied academics and vote-groveling politicians know or care about the hard, usually thankless, and often messy task of finding and building combat leaders?

Unfortunately, we learned the answer to that question just a few years after you wrote your letter, when Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara turned loose his systems analysis Whiz Kids inside the Pentagon, treating the Vietnam War as if it were an Edsel to be conceived, designed, and marketed by Management (them and their bow-tied friends), while Labor (that means us) were supposed to remain quiet and do the dying and just keep those cars coming off the assembly line. But that is the subject of another memorandum.

Your letter. I love that letter. Even now, some 35 years having passed, I take it out and read it from time to time. It was not some cheering, recruiting-slogan atta-boy for my having passed through the wickets of anonymity to try my hand at the elite Trade School that my non-Academy military father had always praised for the quality product it delivered to the operating forces. In fact, the only reference you made to the Academy instead of the Navy at large was to point out that “since the founding of the Naval Academy in 1845 its graduates have served their country with distinction in war and peace.” That was it. No loud ring‑knocking. No recitation of the long list of accolades. No need to parade out Nimitz, Halsey, Lejeune, and Rickover. The Academy existed to produce leaders, and everyone knew that.

Your focus was on the serious task of taking the raw material the nation sent forth every year and finding and developing leaders therein, for the good of the Naval Service and of the country. There were no euphemisms. Your ultimate goal was “to produce an educated leader of character, physically sound, and dedicated to the service of his country.” There were no apologies when you warned that the plebe system was “traditionally tough; not by accident but by design.” You explained that “This is a period of testing—a time to separate the performers from the non‑performers. It requires midshipmen to produce under pressure, to stand on their own two feet, to respond instantly and reflexively to orders, and finally to meet the highest standards of conduct, honor, character, and morality.”

“The highest standards”—a severe and unforgiving gauntlet thrown at my young feet. And there were no promises of touchy-feely counseling sessions if we from time to time failed to meet those standards. You put the onus right back on us by warning that plebe year was “fully within the capabilities of those young men who possess proper motivation.” (Italics…well, you know. You wrote it). And there were no seductive be-all-that-you-can-be invitations to come to the Navy to find the inner me. If I lacked this “proper motivation,” you suggested, I should withdraw my application and pursue another career.

In retrospect it’s almost surprising that I showed up after reading your letter. I was already doing quite well on an academic scholarship at one of the country’s best universities, located not far from some of California’s nicest beaches. I spent many a bleak and nostalgic night over the next four years looking back at what I had given up in order to answer your challenge. I had no desire to have your mandatory engineering degree shoved down my throat. I hated the exhausting viciousness of the plebe system, a regimen so punishing that more than one classmate told me years later he had come through Vietnam fine but was still having nightmares about plebe year. I considered it absurd to be losing even the most normal of college freedoms—no radio in my room for a year, no dating for a year, no riding in a car for nearly three years, no television privileges for three years, having exactly 40 seconds to be out of my bed when the reveille bells went off in the morning, suffering the unbroken, 24-hours-a-day scrutiny of every part of my conduct by those above me—the list, as you know, goes on and on.

But there was something else, not only in your letter but in the eyes of my father and in the hollows of my own subconscious. No, it was not simply the matter of a challenge to my pride—whether I was good enough to endure and triumph in this crucible. It was a summons, up from the depths of the past, glimmering before me like an unwelcome but certain promise: Our history showed that during my adulthood the nation would never be fully at peace, and would most likely at some point be at war. On my shoulders, should I be entrusted with the lives of other Americans in such circumstances, would be the burden of momentous decisions involving life and death. Would I be prepared to do my duty? As I grew older in this profession, I would be challenged to anticipate threat and response to aggression in an ever-changing world. Would I do my part to ensure we as a nation were strong enough to protect our interests and our allies?

The best way to prepare myself for these challenges was to immerse myself in them, both day and night. And so I packed my trash, said goodbye to my surf board, and headed east.

I will admit my stomach did a quick, queasy turn as I crossed the Severn River Bridge and peered over at the wide, flat grounds of the Yard. The cold grey buildings and the tall turquoise poles that marked the outer limits of Dewey Field seemed to delineate a neatly manicured federal prison. And I did not like it very much when the crisp-uniformed upperclassman wearing a red nameplate hit me hard in the chest after I walked out a door and into the true innards of Academy life. And I was more than a little bit amazed when in the course of one quick afternoon everything civilian in my life, from my clothes to my hair to my very speech patterns, were torn, shorn, and beaten out of my countenance. My first night in Bancroft Hall I cried away my youth, knowing that it would be nine years—half as long as I had already lived—before I could make another full decision about my life.

Through the long, dark winter of that first year, as our country slid ineluctably into war in Vietnam, I fell just as irretrievably into your rhythms. Memories visit me even today, mixed with pride and loss. Posting the watch at zero-five-thirty, wondering what was happening back at USC as the nearby stairwells began to fill with plebes jogging up and down the steps as they prepared for their reveille come‑arounds. Trudging around Farragut Field and then Hospital Point in three pairs of sweat gear in the wintry pre‑dawn darkness, watching the lights slowly come on in real homes just across the ice‑clogged Severn River, desperately missing my family, then forcing my mind onto the professional questions that would soon be asked of me. Fighting to stay awake in class, all the while worrying more about what was going to happen to me at the hands of upperclassmen back in Bancroft Hall or at the tables in the mess hall than I did about the remote and seemingly arcane laws of physics and calculus. Days falling into weeks, never with sufficient sleep, feeling exhaustion seeping so far inside me that it seemed to rest like a lead weight inside my bones. Weeks falling into months without the opportunity even to talk to a member of the opposite sex. Asking myself over and over, why did I do this, and why did I not simply walk away and go back to a calmer, more enjoyable existence. And then remembering the proud and somewhat envious face of my own father, who would have given anything to have undergone this misery in order to better prepare him for the demanding task of a military career.

You did not lie to us, Admiral. You made it tough. You held the ring up there, always just a bit higher than we could reach. You held a mirror before all of our faces, daring us to look at ourselves and claim we saw a man who could compare with the great leaders of the past.

That lonely and demanding first year fell quickly into a second, then a third, and finally a fourth. The summers were, as they liked to say, “real world,” with only a minimal amount of leave. One was spent cruising with enlisted sailors on two different ships out of Long Beach, transferring Marines and equipment from California to Hawaii for their further transplacement to the burgeoning war in Vietnam. Another was spent working under junior officers aboard an aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean just days after the 1967 Arab‑Israeli war, chasing the emergent and aggressive Soviet fleet, and monitoring the tinderbox of the Middle East. Inside the Yard, I learned many things, not the least of which was the gut‑wrenching emptiness that comes when one discovers that good friends have died in battle thousands of miles away. One had to process this, as the psychologists would put it today. Could it really be that the hard‑assed, optimistic friend who had lived just down the corridor and walked alongside me on the way to class and joked and crabbed about the adolescent rules of Mother B, and dreamed only of graduation and the future was now dead from a bullet through the stomach in the jungles of Southeast Asia? Was it really true that all of this preparation, all of the timeless lessons about loyalty and courage, could result simply in a quick, unrewarded death? Where did they tell us that in our books and lectures?

The reality was timeless. Our moment had come. We accepted it, inured ourselves to it, and finally came to expect it. This was the world we inherited, those who read your letter and responded to your call. Our fate was to have all of the responsibilities you promised us, yet none of the national adulation that had been given your generation of World War II. But that didn’t matter. Our reward would be in answering the call to duty. We persisted, and retained our pride. Duty, always duty, in addition to resilience under pressure and persistence in the face of loss; that was what your regimens taught us.

You were gone by then, but the young man who walked out of your gates on June 5, 1968, at the height of a war that was tearing our country into shreds, was more than ready. Only some 840 of the nearly 1,400 who had answered the challenge of your initial letter had survived to raise their right hands and renew their oath, now as commissioned officers in the Navy or Marine Corps. By then Your Correspondent was infused with all the challenges of honor, leadership, tradition, and courage, hardened, as military people must always be, against the despair that comes from loneliness and the pain that derives from separation from one’s loved ones. He was ready to lead, wishing only for the opportunity to serve. And in the baking jungles and the blood-filled rice paddies and the murderous mountains he was indeed called upon to serve.

And in service of the principles which have made our nation great, you may be assured, sir, that he is ready still.

Very respectfully,

James H. Webb, Jr.